The postcard that Josie Breen’s husband has received in the mail apparently says only “U. P.” She supplies the uncomprehending Bloom with an interpretive gloss: “U. P.: up, she said.” While this detail has remained a notorious enigma in Joyce studies for decades, its principal meaning seems clear: Dennis Breen is finished, quite possibly mortally. The specific implication may be that he is suffering from a serious mental illness.

Under adverbial meanings of “up,” the OED lists several 19th century uses of the word to mean “Come to a fruitless or undesired end; ‘played out’. Usu. with game” (as in the expression “the game is up”) or, even more to the point, “All up, completely done or finished; quite over. Also All UP (yū pī).”

The usage is also recorded in John Camden Hotten’s Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant, and Vulgar Words, first published in 1859. In a gloss on James Joyce Online Notes, John Simpson notes that “Hotten was the slang lexicographer of the mid-nineteenth century,” and quotes his entry: “UP, […] it’s all UP with him”, i.e., it is all over with him, often pronounced U.P., naming the two letters separately.” In Surface and Symbol, Robert Martin Adams quotes from a later edition of Hotten’s dictionary: “when pronounced U.P., naming the two letters separately, the expression means ‘settled’ or ‘done’” (193).

The OED cites several early literary examples, including J. W. Warter’s The Last of the Old Squires (London, 1854), in which the eponymous protagonist maintains that “It’s all UP—up” is a corruption of an older expression from the English Midlands, “It is all O.P.,” referring to Orthodox (Catholic) and Puritan sects (87).

But the citation that seems most relevant to Joyce is Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist (serialized 1837-39), where the expression refers to a health emergency. In chapter 24 several women and “the parish apothecary’s apprentice” attend the bed of a sick woman in a grim attic room. When their conversation is interrupted by a moan from the patient, the apothecary’s deputy says that she will be dead soon: “‘Oh!’ said the young mag, turning his face towards the bed, as if he had previously quite forgotten the patient, ‘it’s all U.P. there, Mrs. Corney.’ / ‘It is, is it, sir?’ asked the matron. / ‘If she lasts a couple of hours, I shall be surprised.’ said the apothecary’s apprentice, intent upon the toothpick’s point. ‘It’s a break-up of the system altogether.’”

This use of U.P. can be found in later publications. Simpson quotes from Ann Elizabeth Baker’s Glossary of Northamptonshire Words (1854): “‘It’s all U.P. with him’; i.e. all up either with his health, or circumstances.” In Joyce’s own time the application to health emergencies can be found in Arnold Bennett’s novel The Old Wives’ Tale (1908). In the fourth section of chapter 4 a doctor tries in vain to revive the comatose Sophia. He leaves the sickroom with Dick Povey and voices his professional opinion: “On the landing out-side the bedroom, the doctor murmured to him: ‘U.P.’ And Dick nodded.” Some hours later, Sophia dies.

Joyce himself used the expression to refer to his disastrous eye problems. Simpson quotes from a letter he wrote to Valery Larbaud on 17 October 1928: “Apparently I have completely overworked myself and if I don’t get back sight to read it is all U-P up.”

The conclusion seems inescapable: the anonymous postcard is suggesting that Dennis Breen’s life is falling apart, probably because of failing health. As to the nature of the health problems, the characters of the novel clearly think that he is losing his wits. When Bloom urges Josie to observe the behavior of the lunatic Farrell, she says, “Denis will be like that one of these days.” His actions on June 16—tramping through the streets of Dublin, weighed down by bulky legal tomes, to find a solicitor willing to lodge a libel action against an anonymous perpetrator, for the unimaginable sum of £10,000—hardly help to dispel the impression.

In Cyclops Alf Bergan (who Bloom thinks may have sent the postcard) describes Breen as a raving lunatic, and J. J. O’Molloy (who is himself a solicitor) is quick to recognize that Breen’s deranged activity will only confirm the charge of insanity that he is trying to defend himself against: “—Did you see that bloody lunatic Breen round there? says Alf. U. P: up… . / —Of course an action would lie, says J. J. It implies that he is not compos mentis. U. P: up. / —Compos your eye! says Alf, laughing. Do you know that he’s balmy? Look at his head. Do you know that some mornings he has to get his hat on with a shoehorn.”

Despite the strong evidence that the postcard is commenting on Breen’s mental health, readers have sought out other possible meanings. Some are perhaps loosely compatible with the “you’re finished” hypothesis—notably one mentioned by Gifford, that there is an allusion to “the initials that precede the docket numbers in Irish cemeteries.” This interpretation has the advantage of connecting with one textual detail in the novel. In Circe, the caretaker of the Glasnevin cemetery, John O’Connell, refers to Paddy Dignam’s grave with an absurd series of identifying numbers: “Burial docket letter number U. P. eightyfive thousand. Field seventeen. House of Keys. Plot, one hundred and one.”

But the roads most traveled have been sexual and excretory, prompted by reading U.P. as “you pee.” Adams, whose 1962 book was perhaps the first critical study to seriously address the phrase, includes among five possible readings the meanings You urinate, You’re no good, You put your fingers up your anus, and You can’t get it up any more. Only the first of these can be connected very clearly to the letters on the page. Gifford notes that Richard Ellmann proposed the more ingenious but physiologically bizarre reading, “When erect you urinate rather than ejaculate.” An entire M.A. thesis, Leah Harper Bowron’s The Pusillanimous Denis: What “U.P.: Up” Really Means (University of Alabama, 2013) has been devoted to the even more bizarre claim that Breen suffers from hypospadias, a congenital condition in which the male urethra opens on the underside of the penis.

Against these speculations about Breen’s private parts, Simpson sensibly objects that the novel’s contexts do not cooperate with such scabrous inferences: “From the internal dynamics of Ulysses and from the social etiquette of the day (would Mrs Breen show Molly’s husband a postcard with a virtually unspeakable obscenity?) we might regard the “You pee up” interpretation, which has sometimes found favour, to be laboured.”

Simpson adds that the crudely physical and irreverent Molly thinks about the postcard and says nothing about Breen’s genital equipment: “After the I-narrator of ‘Cyclops’ Molly has perhaps the most slanderous tongue in Ulysses. And yet she passes up the opportunity to make a malicious comment on the supposedly obscene allusion behind the wording of Breen’s postcard. She simply regards him as a forlorn-looking spectacle of a husband who is mad enough on occasions to go to bed with his boots on. This is in keeping with the way in which Breen is regarded generally in the novel—the cronies in Cyclops collapse with laughter at his lunatic behaviour, not because of some urinary or sexual irregularity.”

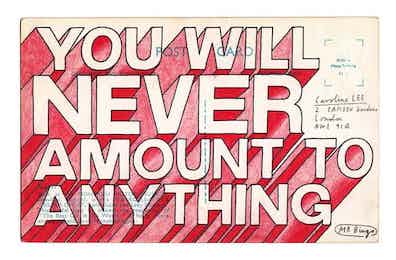

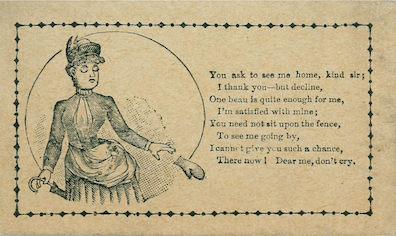

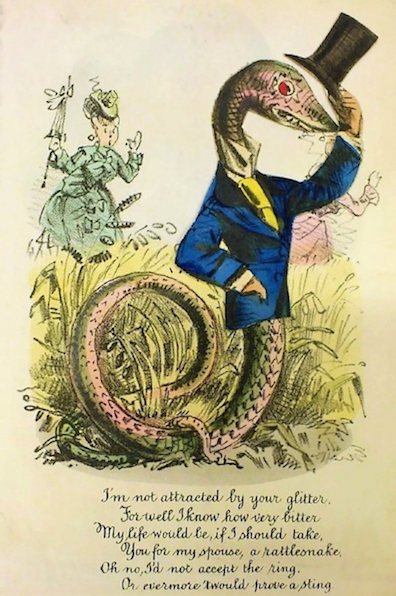

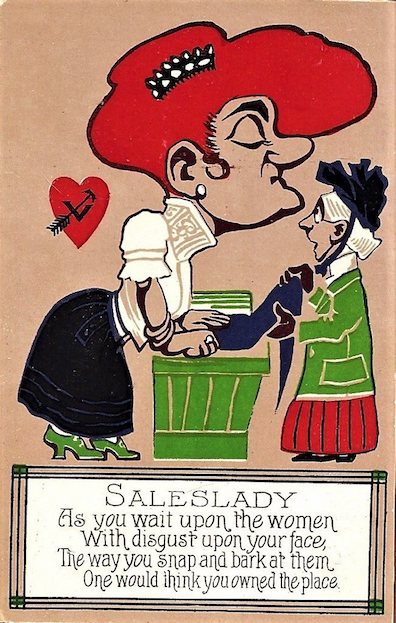

Joyce did not invent the use of postcards to lodge hurtful personal attacks. As Natalie Zarrelli observes in a February 2017 post on atlasobscura.com, one subgenre of the insult postcard, the “vinegar valentine,” goes back at least to the 1840s. People in the U.K. and the U.S. bought mass-produced expressions of romantic disesteem and sent them anonymously on Valentine’s Day. By Joyce’s time other such cards targeted disagreeable salespeople, doctors, and suffragists.

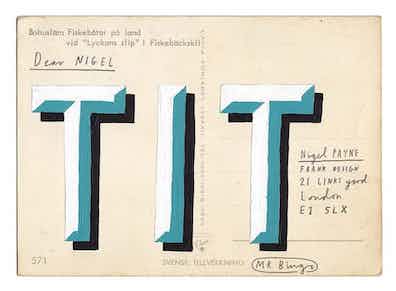

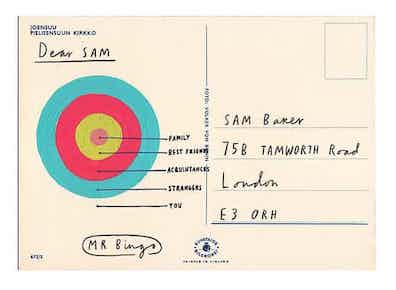

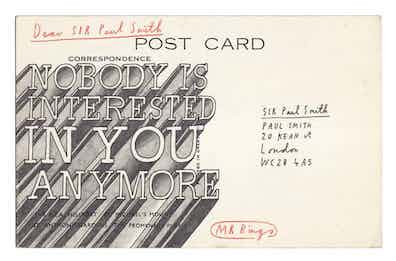

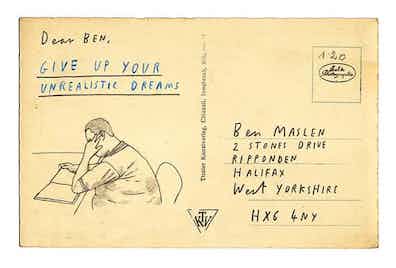

At some point individuals began to be addressed simply for their general insufficiency as human beings. The recent artistic efforts of Mr. Bingo in England, some of which are reproduced here, show that this tradition is alive and well today. It may very well have been alive in Joyce’s lifetime. In Surface and Symbol Adams observes that “on p. 2 of the Freeman’s Journal for Thursday, November 5, 1903, appeared a report of a suit in which one McKettrick sued a man named Kiernan, for having sent him a libelous postcard” (193).

John Hunt 2018

21st century British insult postcard from Mr. Bingo to Nigel Payne, tit. Source: www.theguardian.com.

Another, to Sam Baker. Source: www.theguardian.com.

Another, to Sir Paul Smith. Source: www.theguardian.com.

Another, to Ben Maslen. Source: www.theguardian.com.

Another, to Caroline Lee. Source: www.theguardian.com.

An early vinegar valentine. Source: www.atlasobscura.com.

Another, ca. 1870. Source: www.atlasobscura.com.

A card targeting imperious salespeople, ca. 1910. Source: www.atlasobscura.com.