Dubliners

Hearing Professor MacHugh talk about “the prophetic vision,” Stephen thinks, “Dublin. I have much, much to learn,” and then he announces, “I have a vision too.” In the next section of Aeolus, titled “DEAR DIRTY DUBLIN,” he thinks of “Dubliners” and begins telling his tale of “Two Dublin vestals.” All of this Dublin-focused preamble to the little story of Florence MacCabe and Anne Kearns comments on the arc of Joyce’s writing career and his choice of subject matter.

“DEAR DIRTY DUBLIN” is often attributed to Sydney Owenson, Lady Morgan (ca. 1781-1859), an Irish socialite and writer best known for The Wild Irish Girl (1806). In a survey of sources of the expression on JJON, John Simpson notes that evidence shows “it arose within Lady Morgan’s circle or comparable aristocratic circles in Britain, but does not confirm that Lady Morgan is herself responsible for it.” Linguistic precursors (“Dear, dirty…Scotland,” “dear Dublin,” “dirty Dublin,” “dear, droll, dirty Fabulist,” “dear little Dublin,” “dear little Ireland”) extend far back into the 18th century, and in the 1820s similar phrases (including the “dear dirty” pairing) circulated in Lady Morgan’s upper-class circles. In her Memoirs she wrote that she returned to “our own dear but dirty little home” in Dublin in 1829 after traveling abroad. In the 1830s, the “dear dirty” pairing of adjectives gained wide currency and was sometimes applied to Dublin. In the 1840s and 50s “dear, dirty Dublin” became a common expression.

Finally the origins of the phrase are less important than the ambivalence conveyed in it. In her Memoirs Lady Morgan called Dublin “unfortunate,” “a dreary desert occupied only by loathsome beggars,” the “Wretched” capital of “wretched Ireland.” She loved her native city but found its poverty and filth revolting. This mix of attitudes is maintained in Aeolus. The newspaper-like headline conveys a syrupy tone of sentimental tenderness toward the Hibernian metropolis: our dear home may be a bit tawdry, but we all love it. Stephen’s story, however, draws on the dirty parts. Two over-the-hill, overweight, and half-infirm women from a really dismal area in the Liberties trudge into the commercial heart of Dublin, buy some cheap food, shell out some hard-earned pennies for admission to Nelson’s imperial monument, wheeze their way up the 168 stone stairs inside while piously invoking God and the Blessed Virgin, and collapse on the viewing platform, dribbling plum juice from the corners of their mouths and spitting seeds onto the street below while evidently entertaining some sexual fantasies in the presence of “the onehandled adulterer.” There is nothing particularly “dear” about this portrait.

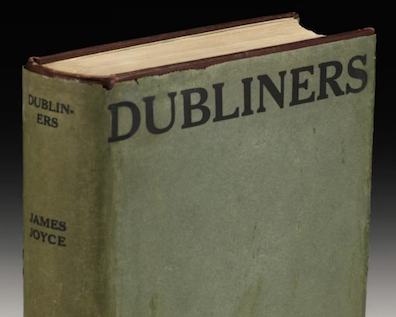

James Joyce took his first small step toward epic artistic accomplishment when he began recording little vignettes of Dublin life that he called epiphanies or epicleti. The religious language did not imply a Symbolist transformation of ordinary experience. It indicated only flashes of revelatory insight into the perfectly ordinary human realities that interested Joyce. By 1906 he had expanded these little glimpses of mundane human life into the stories he called “Dubliners”––one of the greatest short story collections ever––and the manuscript was accepted for publication by London publisher Grant Richards. But Richards got cold feet and did not consent to publish the stories until 1914. Joyce’s letter of protest to the weak-kneed Richards suggests that the miserable tawdriness of “dirty Dublin” was at the heart of the standoff:

It is not my fault that the odour of ashpits and old weeds and offal hangs round my stories. I seriously believe that you will retard the course of civilisation in Ireland by preventing the Irish people from having one good look at themselves in my nicely-polished looking-glass.

Dubliners paints a series of portraits of people fatally mired in dead-end lives, paralyzed by poverty, piety, sexism, alcoholism, colonialism, romanticism, asceticism, and general inertia. Stephen’s story of the two aged virgins is a little more cheerful, but it does not feel out of place among these bleak pictures of human futility. Indeed, it seems to be partly informed by the reminiscence of another couple he saw walking on the beach in Proteus, a gypsy woman and her pimp plying their dismal trade in the same Blackpitts area where Stephen places the two old women’s home: “Damp night reeking of hungry dough. Against the wall. Face glistening tallow under her fustian shawl. Frantic hearts.” His willingness to try out these epiphanic scene-paintings as a pathway to fictional creation (“On now. Dare it. Let there be life”) suggests that he is ready to leave behind his fairly sterile career as a poet and turn toward the writing of prose fiction.

In Joyce’s case this led to the writing of Dubliners, and perhaps Stephen will eventually write some stories himself. But what readers get in his little Parable of the Plums is equally evocative of the methods of the great novel that came next. Ulysses contains all the bleak realities and ruined lives found in Dubliners, but it shows them through the lenses of choice, possibility, affirmation, and hope. It is a book of what the Professor calls “prophetic vision”: Stephen may become the artist he aspires to be, the Blooms may find happiness in their marriage, dark horses may win life’s races, and Ireland may find liberation from England. (This last prophetic prediction proved true in 1922, the same year the novel was published.) Stephen thinks, “I have a vision too,” and if his tale contains one it is to be found at the end, when the two women behave in a sexually suggestive manner sprawled on their petticoats looking up at the statue of the English conqueror.

This is truly parabolic––strange, obscure, as resistant to easy interpretation as the most baffling of Jesus’s tales. But when the two women “lift up their skirts” to Lord Nelson, one distinct possibility is that readers should see them symbolically defying the British empire by casting an apotropaic spell on its representative. This kind of symbolism––perhaps not even remotely available to the consciousness of the ordinary people walking the streets of Dublin, but integral to the greater organization of the book that gives them life––is all too typical of Ulysses. If Stephen intends it, then he shows himself already capable of writing a book greater than Dubliners. But first he has “much, much to learn” about the city that can provide a canvas for such cosmographic generation of meaning.

John Hunt 2025

René Théodore Berthon’s ca. 1818 oil on canvas portrait of Sydney Owenson, Lady Morgan, held in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

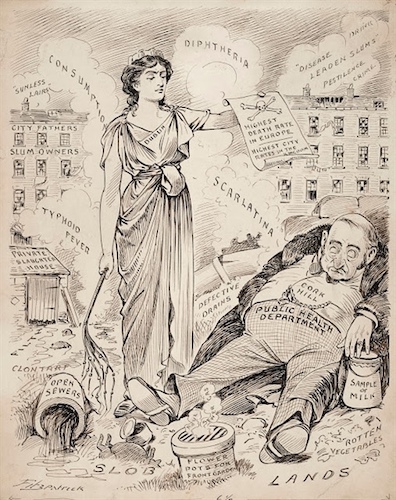

Thomas Fitzpatrick cartoon published in the December 1908 Lepracaun, showing the City of Dublin serving an indictment or eviction notice to the Dublin Corporation, held in the Heritage Centre of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland. Source: heritage.rcpi.ie.

First edition copy of James Joyce’s Dubliners (1914) which went for £86,500 at Sotheby’s in 2013. Source: www.irishtimes.com.